|

Continuing the Photo Tour of my Life in

Flight.

| My first opportunity to fly an aircraft in the U.S. Air Force was in a B-57C when I was

given the flight controls for a time.

While serving as Maintenance/Supply Liaison Officer for the 58th Weather

Reconisance Squadron at Kirtland AFB, New Mexico, I supported B-57C and WB-57F aircraft in

numerous world wide locations. Prior to going to USAF pilot training myself, I was

given the opportunity to fly in the B-57C with the maintenance officer who demonstrated

how the C model was flown both in MAC as a weather aircraft, and in PACAF as a very

maneuverable bomber.

The WB-57F flew at very high altitudes necessitating pressure suits and procedures

similar to those of the astronauts.

|

| My first solo flight was during U.S. Air Force pilot training in a Cessna T-41 Mescalero

similar to this one.

I went through Undergraduate Pilot Training at Laughlin AFB, Del Rio, TX, which at

the time was known as the hardest pilot training base with the highest washout rate.

Visit today's 47th Flying Training Wing at Laughlin AFB.

|

| Very quickly it was on to solo, instrument and cross country training, aerobatics

including spins, and formation flying - both two ship and four ship - in the T-37

Tweet similar to these.

I had one particularly confidence raising experience when flying as wing man on a

cross country at night into Ellington AFB, Houston, TX. As the weather was quickly

deteriorating we did a formation instrument approach in zero visibility conditions down to

minimums and were the last aircraft to land before the field closed due to weather.

Of course, my first solo in a jet, first night solo, spins and four ship formation flying

were all thrilling.

|

| Next it was on to solo and flying faster than the speed of sound - greater than Mach 1 -

plus all of the similar training done in the T-37, only this time in the Northrop T-38

Talon.

First solo in the T-38, and solo in both two ship and four ship formation while

doing aerobatics were sensational. The flight I remember most was a solo flight to a

practice area which took me visually through a thin corridor between two massive cloud

banks reaching from the ground to thousands of feet above me. It was a magnificent

and breathtaking view and experience and I am always reminded of it when I hear the

"High Flight" poem.

Another attention getting experience occurred on about my eighth flight in the

T-38, and only third in the front seat. We were practicing unusual attitude

recoveries, and with my eyes shut the instructor proceeded to put us in an exact vertical

climb with the airspeed quickly dropping. When he gave me the aircraft and said to

recover, I took the appropriate action but airspeed had decreased to such an extent that

the control surfaces were no longer effective. As we slowed to zero airspeed going

up, all warning flags and lights came on. We began to fall directly on our tail for

over a thousand feet and then the nose of the aircraft abruptly flipped forward into a

direct vertical dive. All warning lights and flags were still on though we

determined the engines were still running and had not flamed out. As we approached

our ejection altitude, the airspeed increased, all warning indications disappeared and we

began regaining aircraft control as the air moving over the control surfaces made them

once again effective. We pulled out of the dive and returned to base. After

some research, we found a sole reference to "engine idle decay" whereby air

through the engines has slowed to such an extent that the generators are no longer

operating fast enough to power the aircraft instruments and a power failure indication

with all associated warnings occurs. As air through the engines increased in the

dive, the generators were again spun up and all warnings disappeared. This was a

lesson no one in the squadron had ever experienced and obviously one I have never

forgotten.

With graduation came the Silver Wings of a United States Air Force pilot.

I later flew the T-38 again in the ACE (Accelerated Co-pilot Enrichment) program

while a B-52 co-pilot. In order to give more flying time to B-52 co-pilots, we were

allowed to "check out" a T-38 and do aerobatics, cross country flying, and

instrument and visual approaches whenever we were not flying the B-52 or sitting on alert.

It was necessary to maintain currency and pass all check flights in both aircraft,

and know both the SAC and ATC regulations they were flown under. Upgrade to pilot on

the B-52 had a bit of mixed emotions as you would no longer be allowed to fly the T-38.

|

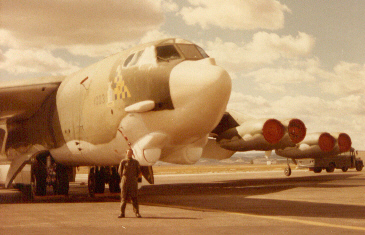

| Following Undergraduate Pilot Training, I flew the B-52F, B-52G and B-52H aircraft.

This included routine celestial navigation legs, high and low-level bomb runs, air

refueling, formation flights and air interception exercises plus many long missions.

I trained in the B-52F and B-52G (shown above) models at Castle AFB, CA, and flew

as a co-pilot in the B-52G and B-52H and aircraft commander in the B-52H at Ellsworth AFB,

SD. I served in both the 77th Bomb Squadron and the 37th Bomb Squadron. These

squadrons along with a KC-135 tanker squadron and the 4th ACCS (Airborne Command &

Control Squadron) comprised the 28th Bombardment Wing. Visit today's 28th Bomb Wing.

A part of a the life of a B-52 crewman included sitting on alert - living in an

alert facility for seven days with restricted movements on the air base, next to your

aircraft ready to go to war. Unannounced exercises would have the claxon sounding at

any time including in the middle of the night. Within a maximum of six minutes, all

crews would start their engines and taxi on to the runway. With seven to nine B-52s

on alert all starting their eight engines with cartridges, and five or more KC-135 tankers

plus an airborne command post doing the same on their four engines, mountains of smoke

would fill the air.

B-52G aircraft used water injection in their jet engines to boost their engine

power for the heavy weight takeoffs which looked like massive air pollution. During

an ORI (Operational Readiness Inspection) the entire Bomb Wing complement of aircraft - 30

bombers, 15 tankers, and 2 airborne command posts - would do a MITO (Minimum Interval Take

Off) which meant an aircraft would start their takeoff roll every 20 seconds , often with

two other aircraft still on the runway in front of you in the midst of their takeoffs.

That's the way you started an all inclusive flight test by the Inspector General

team to determine a wing's readiness to go to war and successfully accomplish their

mission.

|

| Normal B-52 missions included a full day of mission planning and briefings and the

flights lasted from 8 to 12 hours.

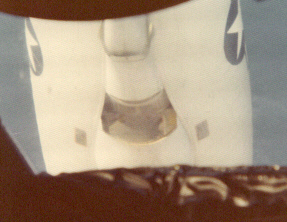

The B-52 (H model shown above) has a landing gear which can be rotated at an angle

to the center line of the aircraft. I have often taken off and landed looking out of

the (pilot or co-pilot) side windows instead of the front windows due to strong cross

winds and blizzard like conditions on icy runways.

The obligatory pictures of myself serving as pilot/aircraft commander. While

sitting on alert, a crew would occasionally have to change to a different aircraft and the

aircraft commander would have to sign for the weapons on both aircraft. During the

four to six hour change over time, he was essentially in charge of the forth or fifth most

powerful nuclear arsenal in the world.

A B-52 crew consisted of the Pilot, Co-pilot, RN (Radar Navigator/Bombardier), Nav

(Navigator), EW (Electronic Weapons officer - also a navigator), and Gunner. The

maximum crew complement of 10 could also include instructors for the four primary

crewmember categories, IP, IN, IEW, and IG.

One of my crews I had the pleasure to serve with - (left to right): RN,

Gunner, Co-pilot, Nav, Pilot, EW) During one Operational Readiness Inspection - ORI

- this crew was the only one in the 28th Bomb Wing to score 100% on all testing, SIOP

briefing, and flight mission exercise getting all simulated weapon releases on target.

The forward panel of the B-52 shows the throttles and engine instruments for the

eight engines, and also the FLIR/EVS screens (Forward Looking Infra Red / Electro Video

System). The pilot's left panel and co-pilot's right panel are shown below.

As a note, the pilots faced forward on the upper deck, the EW and Gunner faced

rearward on the upper deck behind the pilots, and the RN and Nav faced forward on the

lower deck of the cabin compartment.

|

| Pilot proficiency flights usually included a Nav and five or six pilots, and was a four

to five hour flight in the pattern doing instrument and visual approaches to touch and

gos.

Both take-offs and departures (above) and approaches and landings (below) used full

flaps, although no-flap landings were practiced - with a very nose high attitude.

On one occasion in a B-52G we were departing Dyess AFB, TX after a weather

diversion, and while raising the flaps they stuck at 60% down. (With a heavy fuel

load and the gear down we were unable to fly to Ellsworth AFB, SD and returned to Dyess.)

However, all our manuals only had data for Full (100%) or No (0%) flap landings and

discussions with SAC HQ and Boeing found there was no data for any other flap setting as

it had never been done. We proceeded to do "flight tests" determining

stall, approach and landings speeds, prior to doing an emergency landing.

Additionally on landing, the drag chute failed to deploy making the roll out

interesting. The next day after repairs were made (but with a light fuel load) we

again departed, and the flaps again stuck, this time at 40% down. We were able to

fly to Ellsworth at 10,000 feet in a long flight. Again we did our " unusual

attitude flight tests" prior to landing, and again the drag chute failed.

Another interesting mission.

|

| We sometimes flew air intercept missions where we would

fly out over the Pacific Ocean or into Canada, and then try to penetrate the United States

to test the US Air Defense capability.

F-106 F-15 F-106 F-15

Such exercises gave the fighter interceptors a chance to practice - of course we

couldn't use all our defenses (physical and electronic), and we did come in at high

altitude. After numerous intercepts, the fighters would do an ID maneuver and pull

up on our wing. (The B-52s tail guns had a greater range than the fighters, and

occasionally our gunner would get a "kill" prior to the fighter - with the

assistance of some interesting flight maneuvering by we pilots.)

|

| Most missions included low-level flight and simulated

bomb runs on designated bomb run routes. Over most terrain the minimum

altitude was 200 feet above the ground, while in mountainous terrain it was 400 feet

(later raised to 500 feet). Of course we would climb higher over populated areas,

but I have sometimes looked up at campers and hikers on some mountain area bomb runs.

Flying "high" over a prairie town. Pilots' visual navigation and

timing with a stop watch backed up the navigators' electronic and radar navigation.

For terrain clearance we also used the EVS and terrain trace shown below.

During one low level flight, we got engine fire warnings on the two left outboard

engines and shut them down. (Fire damage was later confirmed on landing.) We

climbed out and proceeded on the two hour flight home. After an hour, we began

getting smoke in the cockpit through the air-conditioning system. Procedures called

for shutting down the left inboard two engines, but because we only had some high

temperature indications on those engines, and after conferring with the SAC command post,

I put them at idle since the outboard engines were already shut down. (Upon landing

it was determined we had no thrust from these inboard two engines, and that a very hot

fire had burned a softball size hole from top to bottom in one of the inboard engines and

completely "shelled" - destroyed - both engines.) SAC authorized a

controlled bailout, but I felt I could bring the aircraft back and land safely. Each crew

member was given the opportunity to bailout, but all thought I could get us in and decided

to stay with the aircraft. Several aircraft systems had been lost and many alternate

systems had to be used. After completing all of our emergency procedures and

checklists, I accomplished a successful landing with all four engines out on the left side

of the aircraft. This was by far the most serious emergency I have experienced in my

all of my flying.

|

| Air refueling in the B-52 is the most difficult,

challenging, and yet satisfying flying one can do.

There is nothing comparable to flying a big slow responding aircraft like the B-52

at up to 280 knots while maintaining contact with the KC-135 in an invisible box

approximately 12' x 6' x 3' for over one hour and while taking on a fuel transfer of over

120,000 pounds of fuel. To add additional complications, throw in no autopilot, many

turns and descents (necessitated by increased bomber weight), flying at night with the

Aurora Borealis (northern lights) giving a false horizon at a 20 degree angle to the true

horizon, and the fact that you have already flown for over 5 to 18 hours, and may have

done several refuelings already. My personal longest flight was 27 hours (in the

seat except for the 4 hours between 20 and 24).

We refueled against the KC-135 tanker aircraft.

I obtained many hours of simulator time in the KC-135 with tanker instructor pilot

friends during my free time on bomber alert. I also had the opportunity to go on a

flight to refuel B-52s and take the controls for the first landing (at night) on returning

to base. Besides the tanker instructor, there were two new tanker co-pilots he was

training. As any pilot can attest, once in awhile you get a lucky landing and mine

happened on this flight. I "greased" the KC-135 on to the runway so

smoothly it caused on of the co-pilots to ask if we were down yet. As a smart pilot,

I didn't try for a second landing, and for the next three hours the two new co-pilots

pounded the pavement trying to get close to as good a landing as the "bomber"

pilot made.

Both the tanker and bomber had many fuel controls for all the different fuel tanks

on their aircraft, and great attention had to be paid to where the fuel was being taken

from and put to inorder to keep both aircraft within their respective weight and balance

limitations.

Air refueling from the tanker's perspective.

Pre-contact position with the B-52 in a stabilized prior to coming up for contact.

CONTACT - The tanker boom operator actually flies the refueling boom to contact.

Rendezvous and refueling had to be accomplished regardless of the weather

conditions or time of day - war can occur at anytime. I have refueled in near zero

visibility cloud conditions where you could barely see the tankers wing tips, and at night

at that.

Air refueling from the bomber's perspective.

Pre-contact position with the tip of the boom on the tankers nose.

Just about in contact position. If you looked up through the overhead windows

you could see markings on the boom which showed where you were in the air refueling

envelope which was checked by the non-flying pilot as confirmation. The flying pilot

watched the two rows of lights under the tanker nose on either side of the yellow center

line. One set indicated if you needed to go up or down and the other set indicated

if you needed to go forward or aft in the envelope. The tanker boom operator also

called out the number of feet to go prior to contact, and during contact in case the

lights failed. Yes, we had to practice refueling with the lights off to simulate

their failure.

In contact position looking up through the top window. Refueling was done

both day and night, with and without using the air refueling auto-pilot (like power

steering).

|

| One of the additional duties of an aircraft commander was

to serve as the airfield Supervisor of Flying (SOF).

As SOF, you were responsible for all airfield safety during your eight hour shift

which included inspecting all aircraft prior to takeoff (B-52s, KC-135s, T-38s, and all

transient aircraft like B-57s, Harriers, etceteras), acting as on site coordinator of

airfield activities (working with the Command Post) for aircraft landing with an

emergency, monitoring of alert force exercises, and any airfield incidents such as fuel

spills.

Ellsworth AFB, Rapid City, South Dakota - One half of the flightline showing some

of the B-52s and KC-135s after a brief rain shower.

|

| While flying the B-52, I also obtained my FAA licenses in civil business jet aircraft

and light single engine aircraft. Additionally, in later years I continued my flying

association with the Air Force through the Civil Air Patrol - the official Auxiliary of

the U.S. Air Force. (This will be covered under Private flying - Gliders.) For

now, continue along the professional path.

|

Follow the Thread

Corporate Flying

|